Innovative Latent Print Processing

Nicole Bagley and Monique Brillhart, M.S

FBI Laboratory

See also the instructional videos on "Locating and Collecting Fingerprints"

In the Latent Print Unit (LPU) at the FBI Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, there is a small, specialized group of qualified forensic examiners and photographers who make up part of the Hazardous Evidence Analysis Team (HEAT). Members of this team undergo rigorous training at partner agency facilities across the nation to gain access to a category of unique evidence: items contaminated with chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or explosive materials (CBRNE).

Given the specialized nature of these materials, the standard approach that the LPU would take to examine evidence for the presence of latent prints needed an adjustment. As such, LPU HEAT examiners began adapting their processes and procedures for each unique scenario. One latent print processing technique that the team has taken a creative approach with is known as cyanoacrylate, or superglue, fuming.

Superglue Fuming Basics

One of the workhorses of latent print processing, cyanoacrylate fuming, encapsulates an evidentiary item in a closed chamber and introduces superglue vapors over time to coat the latent prints.

Because of the lack of relative humidity in many locations geographically, humidity is often introduced to enhance the development and success of the technique. This is done to regenerate, or rehydrate, the moisture component of any latent print residue that may be present on the item.

After the item is humidified, liquid superglue is quickly heated until it turns into a gas, which produces vapors that adhere to the regenerated latent residue. Last, the toxic fumes must be purged from the chamber safely.

This entire process results in a plasticized latent print (figure 1) that aids in forensic evidence preservation and print visualization for photographic capture. At this point, that photograph can be digitally transmitted to the FBI Laboratory, where an examiner awaits to analyze and hopefully compare the latent print to any known subjects or search it against the millions of known fingerprint and palm print records maintained in the FBI’s database.

Figure 1. Latent fingerprint developed using cyanoacrylate fuming.

While all of this is accomplished daily for run-of-the-mill evidence using automatic and premanufactured chambers in a controlled laboratory setting at Quantico, the HEAT cases face a different set of challenges. For hazardous situations, the LPU HEAT examiners designed a solution to conduct superglue fuming effectively in a variety of environments.

Creative and Simple Path Forward

Examiners created a specialized portable cyanoacrylate fuming kit designed to deploy easily to any location requiring a HEAT response (figure 2). The kit comprises materials that consider many common CBRNE safety issues and allow for chamber versatility to accommodate evidence items of different sizes.

Figure 2. Cyanoacrylate fuming kit.

To address the need for a safe encapsulating chamber, the kit contains varying sizes and shapes of Schedule 40 PVC pipe and fittings to build the chamber’s framework (figure 3). A Griffolyn Type-55 ASFR tarp is draped over the structure, isolating the evidence (figure 3). This material was chosen because of its robust antistatic, flame-retardant, and puncture-resistant properties, which are key when dealing with evidence that may have an explosive component. Additionally, Griffolyn is an efficient lightweight vapor barrier.

Figure 3. PVC components and Griffolyn.

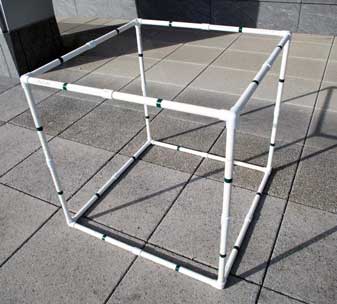

While the kit includes enough materials to build both a 5- and 3-foot cubed tent, the PVC can be configured easily into whatever size or shape chamber is required for the task (figure 4) and covered as needed with the Griffolyn tarp. The prefabricated tent shapes have integrated sleeved ports where hoses can be attached to facilitate humidification and defumigation, as well as a plastic window to visually monitor development. An example of a chamber that can be built using the kit’s components can be seen in figure 5.

Figure 4. PVC skeleton for chamber.

Figure 5. Encapsulating chamber built from kit components.

To obtain optimal latent print processing humidity (approximately 70%) in an oversized chamber, a portable, commercially available ultrasonic humidifier pumps cool mist into the tent with a vacuum hose (figure 6), provided that the evidence will not be negatively compromised or activated by the addition of moisture.

Figure 6. Ultrasonic humidifier.

As a substitute for the electric hot plate that typically would be used to vaporize the superglue, LPU HEAT utilizes CYANO-SHOT, which consists of components to heat the cyanoacrylate in a simple and fully integrated process (figure 7). The number of CYANO-SHOT canisters used and the run time for each fuming cycle is dictated by the size of the chamber. Each deployment kit is equipped to run several cycles as the item(s) is further examined or disassembled. Finally, the defumigation process removes the toxic fumes that are generated and ceases development of latent prints.

Figure 7. CYANO-SHOT.

This simple and portable kit has proven extremely beneficial to evidence analysis in the field and LPU HEAT in support of the Disposition and Forensic Evidence Analysis Team at the Nevada National Security Site. Securing transient latent evidence in the field prior to transporting it to a safer environment yields a better development success rate. Additionally, if the equipment cannot effectively be decontaminated after use and must be disposed of, the basic framing materials are inexpensive and available at most hardware stores. Griffolyn can be purchased in large rolls for custom tenting as well.

This new adaptation of a tried-and-true method is a testimonial that although a problem at hand may be complex, finding an effective solution may be much easier than initially perceived if one thinks creatively.

Disclaimer: This is manuscript 21.02 of the FBI Laboratory Division. Names of commercial manufacturers are provided for identification purposes only, and inclusion does not imply endorsement of the manufacturer or its products or services by the FBI. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the FBI or the U.S. government.

About the Authors

Nicole Bagley, a former forensic examiner with the FBI Laboratory’s Latent Print Operations Unit in Quantico, Virginia, is a senior forensic scientist with the Albuquerque, New Mexico, Police Department. She can be reached at nbagley@cabq.gov.

Monique Brillhart is a forensic examiner and latent print Hazardous Evidence Analysis Team program coordinator with the FBI Laboratory's Latent Print Operations Unit in Quantico, Virginia. She can be reached at mrbrillhart@fbi.gov.

This article appeared in the August 2021 FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. The Crime Scene Investigator Network gratefully acknowledges the FBI and the authors for allowing us to reproduce the article Innovative Latent Print Processing.