Scales, Numbering and Directional Devices

Steven Staggs

© 2014 from the book Crime Scene and Evidence Photography, 2nd Edition

See also the instructional videos on "Crime Scene and Evidence Photography"

Scales and measuring devices

|

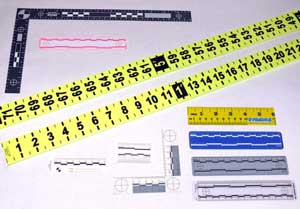

Scales and measuring devices are frequently used in crime scene and evidence photographs. While they are sometime used to orient the viewer of the photograph to the relative size of the object in the photograph, scales are primarily used to serve as a basis for making enlargements to a specified magnification level, such as life size. This is critical for photographs of evidence that later will become the basis for a comparison—such as a photograph of a footwear impression that will be compared with the shoe of a suspect—since a photograph must be printed to life size. A variety of scales must be available for photographing different types of subjects.

- Small self-adhesive scales are used to photograph evidence such as fingerprints and bullet holes in walls.

- 6 inch scales are used for photographing most small to medium sized evidence. Some 6 inch scales have small numbers for extreme close-up photographs and others have large numbers for photographing larger items. The larger numbers allow easy reading of the scale from a greater distance.

- Large “L” shaped scales are frequently used for photographing footwear impression evidence while small “L” shaped scales are used for photographing injuries such as bruises and bite marks.

- Longer scales with large, easy to read numbers are used for photographing tire tread impressions and bloodstain scenes. These long scales can be metal or cloth tape measures or plastic scales.

When using scales in photographs, two photographs of each item of evidence must be taken. One photograph must be taken without the scale in view and one photograph taken with the scale. The first photograph will document that the photographer did not cover or block other evidence with the scale.

Numbering and directional devices

|

Numbering devices are commonly used to identify similar appearing evidence. For example, several bullet holes in a wall would need to be individually numbered. It is usually unnecessary to place numbering devices in a photograph to identify items of evidence that cannot be confused with other items.

When using numbering devices in photographs, two photographs of each view must be taken. One photograph must be taken without the numbering device in view and one photograph taken with the numbering device. The first photograph will document that the photographer did not cover or block other evidence with the numbering device.

Directional devices, most commonly in the form of an arrow, are sometimes placed in photographs to indicate a direction. The direction could be “up” (e.g., fingerprints on a vertical surface) or “north” (e.g., footwear impressions). This helps to show orientation of evidence when the photograph is viewed. Arrows may also be placed in a photograph to point out something that may be difficult to see, such as a lead bullet fragment mixed in with broken glass.

When using directional devices in photographs, two photographs of each view must be taken. One photograph must be taken without the directional device in view and one photograph taken with the directional device. The first photograph will document that the photographer did not cover or block other evidence with the directional device.

Scales, Numbering and Directional Devices Copyright: © 2014 by Steven Staggs. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with publication rights granted to the Crime Scene Investigation Network. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly cited and not changed in any way.

Scales, Numbering and Directional Devices Copyright: © 2014 by Steven Staggs. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with publication rights granted to the Crime Scene Investigation Network. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly cited and not changed in any way.

About the Book

The information presented in this article is from the book Crime Scene and Evidence Photography, 2nd Edition © 2014 by Steven Staggs.

About the Author

For 34 years Steven Staggs was a forensic photography instructor and trained more than 4,000 crime scene technicians and investigators for police and sheriff departments, district attorney offices, and federal agencies. He was also a guest speaker for investigator associations, appeared as a crime scene investigation expert on Discovery Channel's Unsolved History, and provided consulting to law enforcement agencies.

For 34 years Steven Staggs was a forensic photography instructor and trained more than 4,000 crime scene technicians and investigators for police and sheriff departments, district attorney offices, and federal agencies. He was also a guest speaker for investigator associations, appeared as a crime scene investigation expert on Discovery Channel's Unsolved History, and provided consulting to law enforcement agencies.

Steve has extensive experience in crime scene photography and identification. He has testified in superior court concerning his crime scene, evidence, and autopsy photography and has handled high profile cases including a nationally publicized serial homicide case.

Steve is the author of two books on crime scene and evidence photography, the text book Crime Scene and Evidence Photography and the Crime Scene and Evidence Photographer's Guide. The guide is a field handbook for crime scene and evidence photography, which sold over 10,000 copies and has been in use by investigators in more than 2,000 law enforcement agencies.

Steve retired in 2004 after 32 years in law enforcement, but continued to teach forensic photography and crime scene investigations at a university in Southern California.

Article submitted by the Author

Article posted: September 24, 2104