The Impact of Drugs on Human Decomposition and the Postmortem Interval: Insect, Scavenger and Microbial Evidence

Dawnie Wolfe Steadman, Ph.D., D-ABFA, Jennifer DeBruyn, Ph.D., Shawn Campagna, Ph.D., Kristi Bugajski, Mary Davis, Thomas Delgado, Katharina Höland, Allison Mason, Amanda May, Hayden McKee, Charity Owings, Erin Patrick, Sarah Schwing

The University of Tennessee Body Farm, formally known as the Anthropology Research Facility, is a 2.5-acre wooded property where researchers have been studying decomposition in a variety of natural settings since 1981. This research helps us better understand how bodies break down and what may affect that process. It is essential for estimating time of death which, according to National Institute of Justice’s physical scientist Danielle McLeod-Henning “is one of the most important issues to address in any death investigation. Estimation of the postmortem interval can aid in identification of remains, and in cases of foul play, identifying potential suspects and confirming alibis.”

Recently, the researchers noticed an interesting phenomenon. Human bodies donated for study and placed in the same environment at the exact same time were decomposing at different rates. Specifically, they noted:

- Heavy scavenging on some donors while others were completely ignored.

- Insects colonizing the bodies at varying times, despite identical external environments.

- Differing soil chemistry profiles among individuals.

The characteristics of the deceased bodies appeared to enhance or disrupt decomposition. This caused the researchers to question the accuracy of time since death approximations — or the postmortem interval — based on human and insect evidence. They determined that those estimates may contain more errors than has been previously estimated.

Dawnie Steadman, director of the Forensic Anthropology Center and an anthropology professor, and colleagues at the University of Tennessee hypothesized that drugs found in decomposing bodies could have an influence on the behaviors of decomposers and result in differential rates of decomposition. Their study systematically examined the relationships between decomposition and of end-of-life diseases and the drugs (over the counter, prescription, and illicit) in donors’ systems.

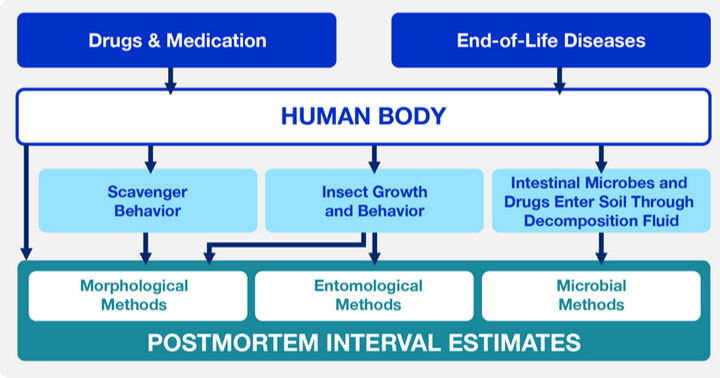

Dr. Steadman’s group analyzed the relationship between a donor’s drug use, end-of-life diseases, and their decomposition dynamics, which are affected by the behavior and presence of scavengers, insects, and intestinal microbes (Figure 1). The researchers wanted to know if drug use altered the expected decomposition rate or introduced unknown error to the estimate of the postmortem interval.

Figure 1. Variables that may affect decomposition and postmortem interval estimates, including drugs of abuse, medication, end-of-life diseases, scavenger behavior, insect behavior, and intestinal microbes. Figure 1. Variables that may affect decomposition and postmortem interval estimates, including drugs of abuse, medication, end-of-life diseases, scavenger behavior, insect behavior, and intestinal microbes.

Decomposition Process is Slowed by Neurological and Cancer Drugs

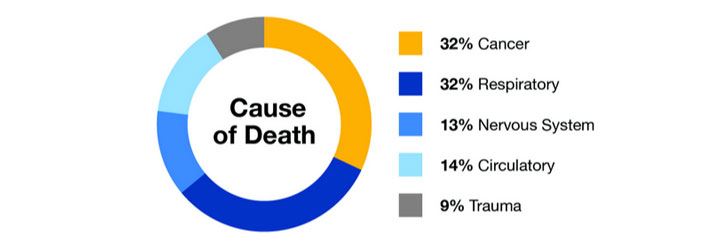

For 22 donor bodies representing various causes of death, the researchers compared the toxicological drug screens of the cadavers to drugs found in their associated decomposition fluid, insect larvae, and soil samples. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A schematic showing the frequency of end-of-life categories represented in this study, including cancer, respiratory, nervous system, circulatory, and trauma.

Dr. Steadman’s team asked if drug use could be tracked across systems that affect:

- The donor metabolome (that is, the collection of substances produced through chemical processes).

- The donor microbiome (the collection of microorganisms in the body).

- The organisms that use the donor as a food source.

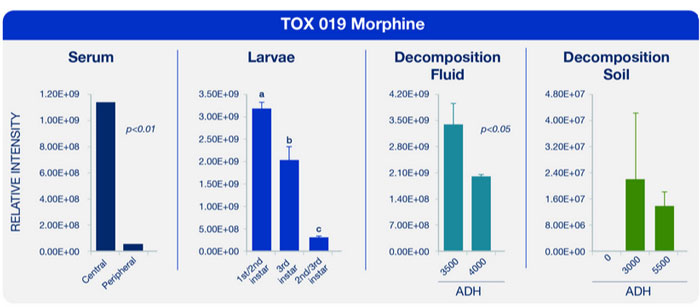

The researchers found that they could accurately track drugs that were initially present in donor blood serum to the insects, decomposition fluid, and soil associated with that individual. Figure 3 shows an example of morphine presence in serum, larvae, decomposition fluid, and soil.

Figure 3. Tracking the route of morphine from the cadaver into the surrounding environment. Table note: Morphine was present in the blood serum, the larvae that were feeding on the cadaver, the decomposition fluid, and eventually the soil as well. Furthermore, the developmental stage of larvae seemed to influence drug detectability, with intensities of detectable drugs decreasing with older larval specimens. ADH refers to accumulated degree hours, which is calculated using the time and the temperature.

The researchers also found that they could correlate changes in insect and microbe community structure and physiology with donor end-of-life diseases and their associated drug treatments. These drug treatments, in turn, affect the overall rate of decomposition. Of note:

- Neurological diseases were associated with a decrease in soil microbial species diversity compared to other end-of-life diseases. This suggests that neurological drugs may have a toxic effect on soil microbes, which leads to a slower rate of decomposition.

- Cancer was associated with a slower microbial respiration rate compared to other end-of-life diseases. This suggests that cancer drugs may have a toxic effect on soil microbes, which leads to a slower rate of decomposition.

- Respiratory illnesses were associated with an increase in soil microbial diversity compared to other end-of-life diseases. This suggests that drugs for respiratory illnesses may have an enhancing effect on microbial diversity and lead to an increase in the rate of decomposition.

“Time Since Death” Estimates Should Take Drug Use Into Account

“This NIJ-funded study delved into the complexities associated with postmortem interval estimation, and the many variables that must be considered,” said Danielle McLeod-Henning.

Although preliminary analysis revealed no statistically significant correlation between end-of-life condition, toxicology, and the accuracy of time since death estimates, the researchers identified patterns that indicate a donor’s drug use influences soil, microbe, and insect characteristics.

This research may ultimately inform how postmortem interval estimates should be modified in the presence of certain drugs. It could also inform the need to perform toxicological testing of different matrices prior to estimating the time since death.